RESONANT ECHOES: THE ART OF BASIL ALKAZZI By DENNIS WEPMAN

It is the rare artist who can successfully fuse style and substance past and present to create work that is both truly timeless and conceptually timely, who can speak with equal clarity to the present and the future. Such an artist is Basil Alkazzi, whose provocative work spans the centuries in both theme and style, treating the universal in thoroughly contemporary terms. The often enigmatic content of his art would be as appropriate--and as challenging--on the walls of a 17th-century manor house as on those of a 21st-century apartment.

The intellectual subtlety with which Basil Alkazzi harmonizes concept and presentation in his richly complex compositions is reflected in his pictorial technique, displaying diverse echoes of expressionism and impressionism, meticulously stylized formalism, elegant minimalism, and abstraction. His use of the figure for purposes of symbolic communication evokes the Symbolist painters and poets of France in the 1890s; the sometimes surprising juxtapositions call to mind the French and Italian Surrealists of the 1920s; the energy of his soaring astral and avian forms suggests the gestural art of the American 1950s. But throughout his long career, through the many stages of his developing vision and his endlessly restless exploration of form, Basil Alkazzi’s skilfully orchestrated compositions have consistently been organized with equal concern for both thematic content and visual design.

As impressive as the artist’s range of style and media is, still more remarkable is the unity of creative purpose he has maintained through the many vicissitudes of public taste and fashion. Through more than four decades of masterly work, he has never deviated from a rigorous adherence to his own aesthetic vision. Although flexible in technique and wide-ranging in subject and theme, Basil Alkazzi has remained unmistakably and unswervingly himself, expressing his sensitive response to the world he sees and experiences in a variety of genres. If he has explored the different modalities with which artists have undertaken to embody their changing perceptions of reality, he has done so from an unmistakably personal angle of vision. His powerful 1961 crayon portrait of his mother--which might easily be taken for an early Picasso--and that of his father in ink from nine years later, is, like the four sensual nude studies of “Desmond” from 1974, evidences of a mastery of line that would do credit to the most classically oriented representationalist. But as early as 1960, in his 22nd year, he was creating semi-abstract figures. The gouache “Portrait” and his works of Christian symbolism of that year are stunningly original in conception. The hauntingly fragmentary “Madonna,” in Fauvist colors, and his torturous “Christ Crucified” strikingly foreshadow the mature artist to come.

|

|

The 1960s also saw a period in Basil Alkazzi’s art that drew on early antiquity. The historical progression in art from the “primitive” to the abstract was to come full circle, curiously linking the primeval images of our remotest antecedents with those of the most contemporary artists. The semantic content of ancient motifs is largely lost to us--we can only speculate about the spiritual concerns embodied in funerary ornaments or the celebratory and placatory functions of cave drawings and heroic monuments--but the pure forms of their archetypal design retain their power, undiminished through the ages. It is a rare sensibility that can awaken the primordial aesthetic and emotional response to these ancient forms within the visual framework of our own age. In a striking series of “Cretan” paintings (1963)--a “Circus” and a “Landscape” in ink--the artist captures something of the underlying dynamic of its archaic sources. In a stylized composition of “Worshipers, Square, & Moon” from the same year, the artist focuses more on the design, emphasizing in the arrangement of his stick-figure celebrants the formal composition of his work and reinforcing his point by his title.

If an exploration of ancient motifs and stylized forms from remote antiquity characterized some of Basil Alkazzi’s work in the 1960s, however, those paintings were seldom without a contemporary element. “Figures in Landscape” and “Lovers,” two boldly faux-naïf ink drawings from 1963, are playfully modern in their suggestive images. More darkly surrealistic are the disquieting “Life & Birth of Dead Foetus” and “Nocturnal Landscape,” both from 1966. As the decade progressed, the artist’s vision darkened further as he devoted himself to a series of nocturnal landscapes featuring increasingly dramatic images of birth and death. “Pregnant Woman & Bird” of 1966 has a visceral quality that evokes the terror of primal nature, the 1967 “Birth & Life” and the series “Lovers & Dreams,” with their vivid contrasts of light and darkness, their flashes of lightening, and their stark imagery, are both haunting and disturbing. The oneiric 1968 “Mother and Child” and “Bird Fleeing Death” are even more so.

Basil Alkazzi’s early visions were not always disturbed or disturbing. His series of “Seascape with Fish” from 1973-74, their neatly patterned figures gliding along an equally neat and symmetrical shore, have an engagingly child-like innocence that reflects a serene spirit, and even the work specifically identified as inspired by dreams is peaceful. His 1970 collage series “Landscape of Dreams,” in fact, seems not only serene but even, in places, joyous, though the artist himself has added a melancholy note in reference to these three pieces. “The tragedy with dreams,” he wrote in 1970, “is that they are so solitary, the other person is seldom consulted, so that, when it comes to assembling it, like a jig-saw puzzle, the other person, the other piece does not fit in, does not want to, or can’t. Perhaps they belong to a different picture--someone else’s dream.”

The human figure remains absent, or nearly so, in much of the work of the late 1970s, but the human spirit is clearly evident. The “Night of Glorification” referred to in two paintings of 1976, and “Come, the Night of Glory Has Come” of the next year, do not specify what is glorified, or by what, but the beneficiary of the glory is clearly human. And the 1976 “Birth of Creation” is exultant. Love, in fact or in prospect, begins to dominate the artist’s work from this period. It is sometimes explicit, clearly corporeal, as in the two “Transmutation of Lovers” and the disturbingly titled “The Lover and the Killer Are One” from 1980, all fusing the bodies of their subjects. Basil Alkazzi’s seascapes have by then abandoned their fish and are clearly anthropocentric. “Seascape with Figures I and II” of 1981 focus, in fact, on the figures almost exclusively; the viewer must take the artist’s word for the sea behind or beneath them. The figures in these paintings, like those in the “Lover” pieces, are stylized, to be sure, but unequivocally human, solid and richly modelled in warm flesh tones, radiant against the dark backgrounds.

The love celebrated in Basil Alkazzi’s paintings of the early 80s is not always erotic, however; increasingly it is rather spiritual than sensual. As George S. Whittet has noted, “During the 1970s a covert element of mysticism invested the paintings. . . . By the early 1980s after an interlude engaged with the theme of lovers at much closer range as symbolic, earthbound and sculptural masses, [Alkazzi] resumed his search for material resolution of inner subliminal compulsion.”1 In the 1982 oil painting “Transmuted Lovers & Flight…I,” the lovers are still apparent, seen distantly and dimly through the arch of a cold and forbidding edifice, but they have been transmuted far more than those in the 1980 “Transmutation of Lovers,” overwhelmed by the mysterious structure surrounding them and the dark night sky above. They have disappeared entirely from “Awaiting Birth of Soul,” “A Soul, Awaiting the Moment,” and “O Contented Soul, Return to Thine Abode, Blessed and in Peace,” the highly spiritualized paintings of the same year. The figures, barely perceptible in these paintings, are not bodily lovers; they have been transmuted to pure spirit and move serenely on their ethereal way.

|

|

|

Although the artist’s work became increasingly spiritualized and abstract in the 1980s, he never lost his grounding in reality and physical form. His early experiments with collage, surely the most substantial medium presented on a flat surface, did not end with the 1970 “Landscape of Dreams” pieces. The same year he explored the possibilities of portraiture in fragmenting photographs of Liza Minnelli, entitling it “Liza Minnelli and Liza Minnelli” to show the two “faces” of an actress and a private person and how they interact and express themselves within a picture frame, a living moment of time. In 1985 when, temporarily handicapped by a strained tendon in his arm and unable to paint, the artist sought another channel for his creativity and began to play with the idea of photo-montage. Images formed by composing elements from separate photographic sources, photo-montage had been around since the Dadaists, and the term had been in use since 1918, but the medium had not been widely known until a show by David Hockney introduced his “photo-collages,” as he called them, at the Emmerich Gallery in New York City in 1983. The exhibition opened to mixed reviews; Stuart Morgan wrote of it in Artscribe, “An applied style kills the subject and makes the whole business little more than a technical exercise,” but the British Journal of Photography described the show as “the single most important photographic exhibition for over ten years.” Like David Hockney, Basil Alkazzi composed his photo-montages of elements from many photographs of the same subject. His “Patti Palladin, 3 Ibis & No Craw Fish” comprised elements of 103 or so photographs, and “Ronald Kuchta & Glasses” comprised 60 or so. In both the artist achieved a dynamic sense of movement by deliberately moving the camera as he photographed.

A personal diversion with no thought of exhibition or, like David Hockney’s work, the production of editions for sale, Basil Alkazzi’s photographs were all of people he knew, some of them old friends, some recent ones, but all sharing personal relationships with the artist. The subjects are all posed and stationary, but many achieve that quality of “snap shot” movement. Part of the kinetic effect derives from the artful use of formal elements within the images themselves. “Tim Powell and Stripes” and “Ronald Kuchta at 11:15” (1987) both depend on the broken arrangement of the striped patterns on their subjects’ shirts. (The hour in the latter title refers to the position of the hands on Kuchta’s watch in the picture.) “Ronald Kuchta & Glasses” makes a seeming patchwork of its model’s jacket, and it is also the fragmentation of her luxurious clothing that provides motion to the glamorous portraits of Eva J. Pape. The humorously named and composed “Vivienne Thaul Wechter & Bruised Toe” (1988) appends its solemn subject’s swollen toe in an isolated segment as a sort of jocular footnote. A small collection of these pieces was exhibited at Fordham University and was issued in book form in 1988, but the artist makes no very serious claims for his work in this rarefied medium. He pursues photography, as he has stated, whenever there is a lull in his painting, “as an alternate form of creativity.” Its status doesn’t worry him. “Is it good art? Bad art? Or is it art at all?” he asks rhetorically. “Frankly, I don’t care. I enjoy it, and that is all that matters.”2

While transferring his need to create into this form because of the injury to his elbow, Basil Alkazzi never stayed long away from the serious business of his life. In the middle 1980s, his art became less concrete, more deeply visionary, his symbolism sometimes obscure but always gripping. Such mysterious (and mysteriously entitled) paintings as “And Still They Whisper, Still You Whisper, Still They Wait” (1986) show stylized figures huddled in two groups at the arch of one of his hieratic buildings, immersed in unfathomable conversations. The composition is hypnotizing in its elegant balance, the content intriguing in its mystery. Equally tantalizing is the series of three paintings from the next year, “Transmutations in Time,” their spectral human figures moving beneath heavenly bodies unknown to our astronomy in a dark night rendered in deeply saturated cobalt and purple. Other 1987 paintings reveal the recurring motif of the triangle, an ancient arcane symbol Basil Alkazzi utilizes in his elegant personal logo and uses here with profound effect. The series “Wait, Look, See How It Comes, Across the Isthmus” and “And Now It Comes, See How It Comes, the Seal of Love,” employ the geometric shape in multiples, superimposing the triangles to form the traditional Hebrew symbol known as the Seal of Solomon, beneath refulgent skies teeming with huge rushing planets, and vast slashes of brilliant light cleaving the opaque night. These motifs continue into the 1990s, but the range of color grows; “Transmutations III, IV, V, and VI,” a 1991 series of gouache paintings, present the familiar circle and triangle, huge and incandescent, in subtle tones of purple. Deeper shades appear, rich gold and blues that verge on black, in the heroic 1992 series of thirteen gouaches “The Last Supper,” now in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

“At this time there was a change of direction away from the non-objective, though still symbolic painting to the extraordinary group of figures on the theme of The Last Supper,” the critic Max Wykes-Joyce has written of this series. “In selecting the theme, Basil Alkazzi has aligned himself in a tradition which runs in Western painting from the Fourteenth Century to the present day, from Fra Angelico to Stanley Spencer. Skilfully he has avoided wearisome comparisons with past paintings and with historical imagery by the portrayal of the hands of the participants, Jesus of Nazareth and his followers, and the ritual wine cup which went its rounds at the supper table.

|

|

Viewed dispassionately, they might be well described as a very odd group, including among them four fisherman- two pacific and two of such vehement conviction they were named the Sons of Thunder; a carpenter; a tax inspector; a nobleman; and a disaffected and disappointed militant. Each is represented and revealed in Basil Alkazzi’s The Last Supper by no more then a pair of hands in conjunction with a wine goblet, itself moving into medieval history and ritual history, as the Holy Grail. The predominant colours of the Supper sequence are the golden flesh tints of the hands and the gold of the wine cup against a night-sky-blue background and jet-black foreground.”3

Dream, memory, spirit, love, time, all return again and again as motifs in Basil Alkazzi’s œuvre, endlessly varied in composition, association, form, and color. No less pervasive is the theme of progression, the elevation of the spirit, represented now as an idealized ascending form, now as a heavenly body. In the inspired and inspiring 1996 gouache “Blossoming Moon in Skyscape II,” in the collection of the Neuberger Museum of Art at the State University of New York at Purchase, the soul is presented as a swelling moon tracing its path across the night sky as it advances from dark to full maturity. Scale, essential to the magnitude of the theme, is an essential element in the impact of this eight-part painting, which measures almost three by more than fourteen feet. “A Fragrance of Dreams III,” executed the next year and now a part of the permanent collection of the Dayton Art Institute in Ohio, is more clearly defined in its symbolism but equally positive in its message. It depicts a solitary soul drifting upward, illuminated by an arc of luminous moons, radiantly traversing the cerulean heavens.

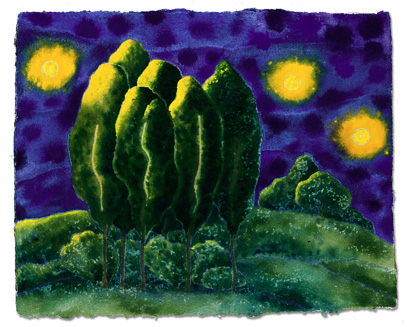

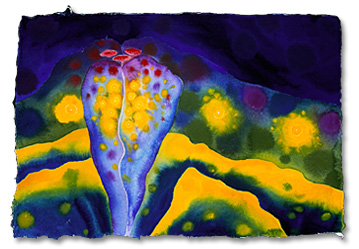

In 1999-2000 after a move to the South of France, the artist varied his serene mysticism, turning from sombre blues to throbbing yellows and vibrant greens in richly sensuous compositions. Abstraction is ordinarily the most austere mode in the plastic and graphic arts; intending no precise representation, whether derived from nature or from pure formal invention, it need evoke no associative response, dealing with the universal rather than the particular: form unencumbered by substance. But not all abstract art excludes the physical world from its content. Picabia, Arp, and Miró all painted “non-objective” but biomorphic images more or less clearly evocative of nature. In Basil Alkazzi’s gouaches in the “Rites of Spring” series, the swirling protoplasmic shapes and the burning yellows of his abstracted flowers display a compelling emotional energy. Abstraction may aim at appealing to a chaste intellectual spirit by stripping its subjects to the bare bones of form and color, but no one can look at the incandescent figures in Basil Alkazzi’s work of the turn of the century without realizing the resources of sultry sensuality it can summon. The resplendent flowers of “The Rites of Spring,” the rich-hued skies alive with planets, suns, and moons hurtling through infinite space, the swirling forms balancing the cool shapes of classical geometry, provide a great range of aesthetic impact.

Basil Alkazzi’s imagery expresses a mysterious and complex personal vision with a magnetic force that draws us at times inward and at other times into infinite space; it spans the microcosmic and the macrocosmic, the poised and the kinetic, protozoa and planets, the autochthonous and the celestial. In his Rites of Spring he is as richly allusive and at the same time as innovative as Stravinsky, from whose ballet he may have taken the title of the series. Like the composer, he is an artist, who creates from within a framework of profoundly interior association, his luminescent canvases always a projection of a personal vision of reality expressed in a uniquely private iconography.

The critic Donald Kuspit has observed, “Basil Alkazzi has found the vital archetype of cosmic nature within that of mundane nature. He shows that what seems to be hollow form has an archetypal content. The rich colour and dynamic line go a long way towards convincing us that his life-force flowers and heavenly objects have archetypal import—towards re-originating them as spiritual entities, indicating that natural life is simultaneously spiritual life, and as such a sign of the spiritual purpose and sacred character of the cosmos. His life-force flowers blot out the horizon or boundary between heaven and earth, and he shows us heavenly objects about to burst through it, suggesting that the separation of natural space and cosmic space—implicitly matter and spirit—is far from absolute. It is only in this regard that he disagrees with Emerson, who declared that ‘the health of the eye seems to demand a horizon.’4 Basil Alkazzi shows us that the eye is really healthy when it can see beyond the horizon, without any frame for its consciousness.”5

The archetypes that Basil Alkazzi has evoked throughout his working life follow the inner logic of the artist, reflecting a mythology of his own. Enigmatic, provocative, sometimes disturbing, his private language may challenge reason and compel the viewer to accept the work that employs it on its own intellectual, spiritual, and aesthetic terms. It never stoops to the literal, though it sometimes uses the literal to evoke and represent the supernal. As Donald Kuspit has noted elsewhere “Basil Alkazzi’s art . . . is a sacred, spiritual art, for it unites images of sacred geometry and sacred life. Abstraction is the best way of invoking the sense of the sacred, if only because it eliminates the appearance of the everyday world. . . . Transcendental ecstasy is Basil Alkazzi’s ultimate subject matter.”6

The relevance of his work, and indeed of all art, raises a fundamental question for Donald Kuspit, who asks, “What has art done for humanity?” and answers himself eloquently: “In asking this question, I am aware of what science and technology have done for humanity. A special issue of Newsweek documents ‘The Power of Invention,’ more particularly, ‘How an explosion of discoveries changed our lives in the 20th century.’ How has 20th century art changed our lives for the better? That is the question that has subliminally informed my discussion of Basil Alkazzi’s art, which offers one answer—an answer that places it in what for me is the grandest tradition of twentieth century art. His art, like that of Kandinsky and Rothko, keeps alive a sense of spirituality in a century that, however materially glorious, has been spiritually bankrupt, with devastating emotional consequences for its inhabitants. Like their art, Basil Alkazzi’s art is concerned with what Kandinsky in Concerning the Spiritual in Art called ‘the all important spark of inner life’—in the modern world ‘only a spark.’ It is implicit in the ‘inner meanings’ or ‘spiritual vibrations’ of colours, which seem to have a life of their own. Like Kandinsky’s and Rothko’s subtle art of color, that of Basil Alkazzi ‘endeavors to awake the subtler emotions, as yet unnamed,’ than those that occur in the course of everyday life—emotions that sparkle with, and seem a source of, inner life.”7

The first decade of the 21st century has seen a shift in Basil Alkazzi’s focus as the esoteric imagination of the previous few years has made way for a return to the solid forms of nature, but with no less of the “transcendental ecstasy” noted in his more abstract Rites of Spring. The enigmatic imagery of that series painted in 1999 and 2000 was transformed into more clearly organic forms, equally intense in spirit and at times equally personal in their symbolism. Among the most powerful of these works are series exploring times of day (Dusk, Twilight, and Sunset in 2002 and 2003, all as rich with personal iconography as his earlier work), the seasons (Blossoming Spring in 2003, at once passionate and lyrical), and several classical landscapes in that same year. For the moment, the compositional elements that recur through much of the artist’s earlier work are absent, and he dwells on the natural world with a kind of tremulous nostalgia.

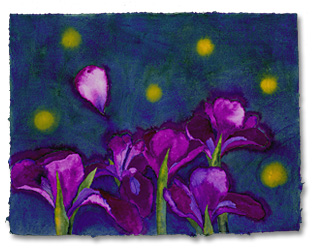

“I used to look inward and heavenward for inspiration and expression,” the artist has written, “but since moving to Monaco in the South of France my whisperers have altered my creative vision, directing it to the heaven on earth. . . . “ More concrete, more focused on reality, and perhaps on that account more rapturous, his work in the last few years has descended to the earth thematically but ascended to the stratosphere emotionally. The influence of his Mediterranean surroundings is perceptible in the warmth and vibrancy of his presentation, in the poise and serenity of his personal tone, and, in recent years, in his choice of subject: lilies explored in all the amazing shapes and colours of that aristocratic genus through 2004 and 2005; the sumptuous iris in 2006 and 2007. These natural jewels have provided material to artists for centuries, but each brings to his perception of them his own sensibility. The rich colours of Basil Alkazzi’s florals are chromatically accurate, but they have a clarity and vibrancy that give them a dimension not found in mere horticultural illustration. The forms are organic, solid, and controlled, but it is the interplay of hues that creates the vital colour landscape outside of and above the literal reality they depict. In sharing Basil Alkazzi’s response to his subject, we never lose sight of the fact that we are seeing something more than the natural form; we are seeing the artist’s spirit, expressed in his own unique aesthetic language.

If the interpretation of these paintings is sometimes demanding, it is also exhilarating. The imagery seems private, but it is never without a universal relevance that transcends the particular, and in this it compels the viewer to provide that final element of personal involvement necessary to the complete experience of art. It is one of the most exciting aspects of Basil Alkazzi’s painting that he credits us with the perception and the spiritual maturity to do so. His message is not always clearly articulated; we are compelled to participate in the creative act. But the work is not hermetic. If he works from a personal vision, his art is not only accessible but richly rewarding to those emotionally and aesthetically open to the experience it offers. Basil Alkazzi is singularly in touch with his own spirit and his own world view; if he does not demand that the viewer share that view--and there is nothing strident in the tone of these masterfully self-contained works--he impels an emotional and an intellectual response by the passionate artistic integrity of his work, and by the depth of feeling that informs it.

1 George S. Whittet, Mystic Dreamscapes: The Art of Basil Alkazzi (Brooklyn, Conn.: NECCA1988).

2 Basil Alkazzi, Portraits: Strangers No Longer Strangers, Now Acquaintances, Friends, Lovers. . . (Brooklyn, Conn.: NECCA 1989).

3 Max Wykes-Joyce, Basil Alkazzi--New Seasons… (Jersey, CI: Izumi Art Publications Ltd. 1993).

4 Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature, Addresses, and Lectures (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1979) p.13.

5 Donald Kuspit, Basil Alkazzi--The Rites of Spring (Jersey,

CI.: Izumi Art Publications Ltd. 2000).

6 Donald Kuspit, Basil Alkazzi--New Horizons. . . . (Jersey,

CI.: Izumi Art Publications, Ltd. 1998).

7 Ibid.

|